Modular indirection is the best direction

(If you think this title is bad you should see how I name variables!)

Whilst I worked at the Guardian I worked in a monolithic codebase. The majority of code lived in a single module. This had the expected downsides:

- slow incremental builds,

- hard to discover code

- quite a bit of known, but hidden, complexity!

Our aim was to increase modularisation. This would bring faster incremental builds and increase better engineering practices. With lower coupling and increased cohesion we will see better code. We also had business goals to increase cross functional collaboration. Modularisation should encourage this.

Modularising unearthed some impressive levels of coupling and a general lack of cohesiveness. Let’s not talk about our Dagger set up! This melange made it very difficult to break apart our monolith.

It became clear that to tackle this problem we needed to standardise our approach. So, as with all good projects this meant a good deal of investigation into the best approaches.

There were two sources I kept coming back to over and over again:

- Ralf Wondratschek’s talk called Android at Scale @Square.

- Nacho Lopez and César Puerta’s talk called Scaling Dagger DI in a Modular World

Both talks give excellent insights into the world of modularisation in large codebases, it also gives insight into how we can tackle this with dependency injection (this post is going to avoid dependency injection in detail because it deserves it’s own!). I regularly re-watch those talks and I feel like I pick up on something new every time I watch them. Here are some top-level topics that both talks cover:

- Creating modular code bases that don’t compromise on build speeds

- Making good use of dependency injection (Dagger @Square and Scythe @Twitter) in a modular code base

- Moving our monolithic code (:hairball, @Square and :legacy @Twitter) into smaller modules

I left the Guardian and joined Twitter before we made large amounts of progress. Twitter is much further along in the modularisation process discussed above. It is so exciting to see something I have spent a whole year thinking about in action.

Over this year I’ve done a fair bit of thinking and prototyping based upon the talks above and from my own ideas. I’ve gotten to a place where I am happy with what I’ve come up with. I will write a series of blog posts to delve into the benefits and some tooling ideas I have floating around in my head.

This post explains my mental model of a problem we want to solve. Provide some concrete examples of a solution and then validate the improved approach.

The Gradle graph

I am not a Gradle pro, I am working on a mental model that I think makes sense. Would love some feedback on this!

Lets look at how Gradle and build a mental model to look at the problem. I’m going to come back to this mental model a number of times in this post.

An important primitive in the world of Gradle is a project, commonly referred to as a module. We can spot a project as it is a directory containing a build.gradle file. Gradle projects have 0..n nested sub-projects. Projects can nest content like code or resources in other sub-directories.

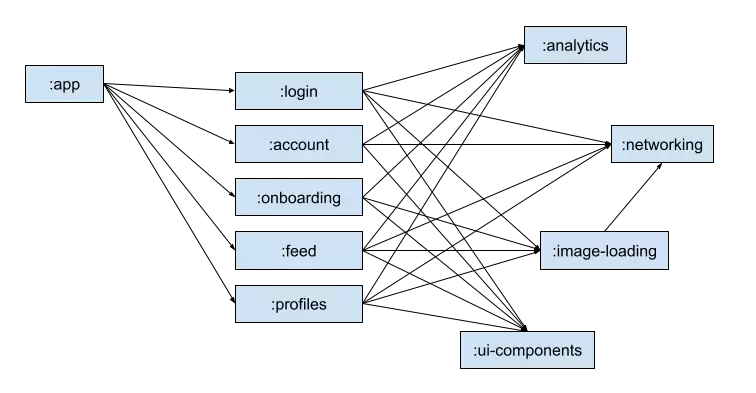

Gradle builds a directed graph, this is a graph where the edges between nodes have a direction. We can not create a circular reference in a directed graph. Nodes are projects. Edges are relationships defined by a Gradle dependency e.g. implementation, api or kapt.

Changing the code in a project invalidates our project or any related projects. In the above example, a change in the :networking module may invalidate the six other modules.

In general the code in each of these modules recompiles (not always true, but it is true in this mental model). We can push our black box of knowledge a little bit deeper by looking at what is a task.

Tasks

A task is an idempotent piece of work that Gradle may execute to do a job. Because it is idempotent, Gradle is able to cache the result. If inputs are the same as a previous running of the task we know that we can use the cached result.

Every Gradle plugin contains a set of tasks. For example, the Kotlin JVM plugin contains tasks that compile using kotlinc. The kapt plugin contains tasks that create java stubs from Kotlin files. The Android application project contains tasks to generate an AAB or APK. Tasks are added to a project by applying a plugin to a project. The plugin helps us to identify the type of project we are working with.

Task invalidation

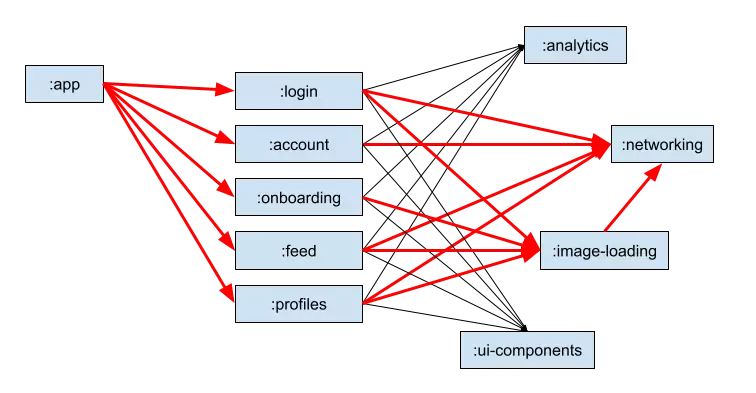

A Gradle task invalidates when new inputs to a task differ from the inputs to a cached version. The task must now be re-run to produce a new result. An input to a task can be a file or even the result of another task. Tasks may cross project boundaries and can validate another project’s tasks. This explains the large quantity of red arrows in the last graph.

Incremental compilation is when Gradle only runs invalidated tasks. We want to keep invalidated to tasks to the smallest. This means reducing the number of edges in the graph. The more modules that need to be recompiled the longer your incremental builds may be.

Our job as developers of a modularised codebase is to maintain a healthy project graph. As we begin to modularise a monolithic application we will see an improvement in build time. If we don’t manage this correctly, our invalidated project graph will begin to rival the incremental build time of our monolith.

Another benefit for Gradle enterprise consumers is that smaller cached tasks can be easily shared across many users. We will begin to see improvements in our clean build time for developers.

Tackling with indirection

To resolve this we can make use of a bit of indirection and play some tricks with Gradle to reduce invalidated tasks.

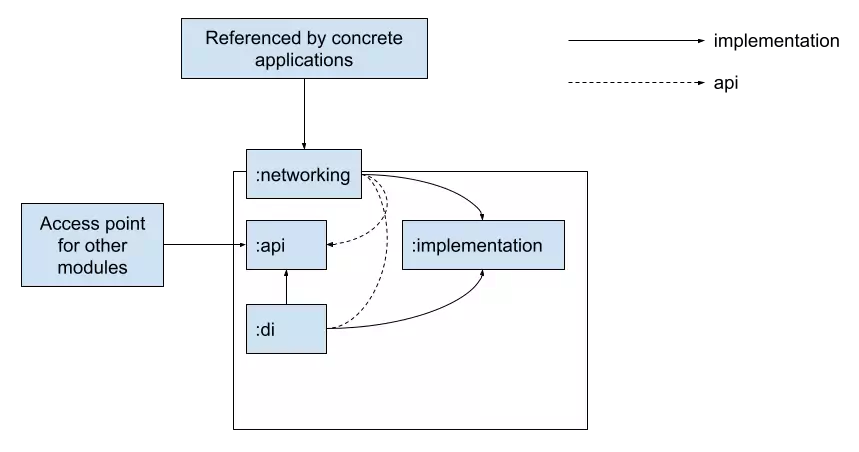

The talks linked to above all suggest an architecture that divides an :api from an :implementation. Let’s delve into this a bit deeper. Top-level projects must be split into at least three smaller projects:

- :api – Defines a static api that other modules can use

- :implementation – Contains implementations for all abstractions defined in the :api module

- :di – This contains the code that wires together the :api to the :implementation.

There are a few rules. Other projects that want to use our feature should only refer to the :api project. The : implementation module should only be consumed by a com.android.application project and the :di module.

You may notice that the parent :networking project references all internal modules, :api, :implementation and :di. This is not necessary but I like this as it allows our com.android.application modules to create a manifest of all required modules.

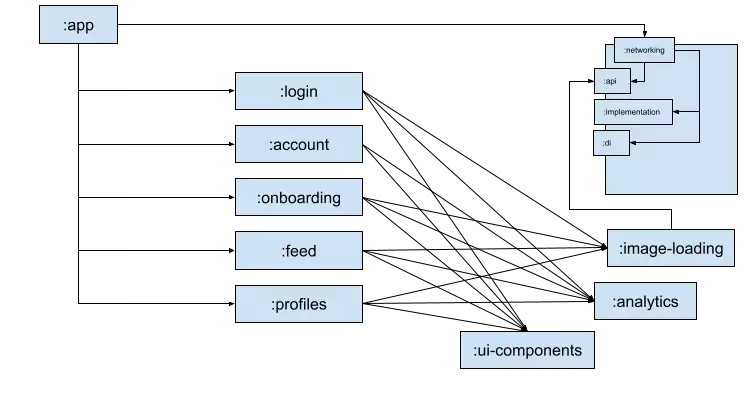

Let’s recreate our first project graph again with our new :networking module structure.

Looking at this graph again we can see the improvement this should make. We’ve reduced the number of direct edges to our volatile :implementation module. Imagine invalidating the :implementation module we can see it has a much reduced impact when compared to :image-loading.

There are a lot of interesting ways we can take this module structure. It simplifies creating one off applications ( called sandboxes at Twitter), we can nest our tests and separate our fakes.

The eagle eyed among you may notice that the :di module also references the :implementation module. This allows our :di module to downcast our implementations into the abstractions contained in our :api module. Like I mentioned above, this really deserves it’s own blog post!

Validation

Wouldn’t it be great if we can validate that this approach actually brings the improvements I am promising. Well.. I can’t prove this right now but I have some ideas and it is actually the reason I wrote this blog post.

I plan to create some tooling that can be used on a project implementing a module structure as I’ve defined above. The tooling will live within Android Studio/IntelliJ or separately through CI tooling.

Invalidated Tasks

We measure our builds using time (or success or failure). Time has many variables:

- your machine (slow/fast processor),

- concurrent processes (1 or 100 browser tabs open)

- or the status of your local Gradle daemon.

Gradle has another indicator: measuring the number of tasks invalidated by a change. Whilst not giving us a concrete time impact we can infer the impact of those invalidated tasks.

Searching the graph

We can validate a two properties if we look into the shape of the Gradle project graph:

- An :implementation module should only have a depth of two from a com.android.application node

- Any :implementation module should have one direct sibling with an implementation edge (:di) and another reference from a parent module (it may have one or more testImplementation)

If these properties are true, we know we have created an isolated :implementation module. We can safely change without worrying about the impact of our changes throughout the rest of our project graph.

Property #1 is validatable by finding an application module node and starting a depth-first search from that node until we have found every :implementation module throughout our code base. If we find a module after visiting more than two nodes we know this module needs to be improved.

We can confirm property #2 by confirming that every implementation module is visited twice. If we encounter it more than twice it is an indicator that the graph is incorrect.

I hope this has been interesting for some developers out there, but this post has gotten a bit too lengthy! The next post in this series will talk about dependency injection in a modularised world and look into how the directed graph of dependency injection can work alongside our project graph!